The Story Grid by Shawn Coyne does not guarantee success when writing fiction or narrative nonfiction. It is a study into the form of a story, something that is built into every human at an instinctive level.

My AI assistants suggest outlines, topics, or subtleties I hadn’t considered. The actual writing is all human me. It’s fun seeing how the different Gen AI models sometimes give contradictory advice. I ignore most of it anyway.

We all know when a story works and, conversely, when it’s clunky and unstructured. But if we were to ask a reader to pinpoint the exact issues with a story, we’d likely receive vague responses like ‘it felt off’ or ‘it didn’t flow.’ While these answers are a start, they don’t provide the clarity we need. The Story Grid methodology, however, can bring that much-needed clarity to your understanding of storytelling.

Last week’s newsletter was all about the research required for a work of fiction and the structure or form of a working story. This week, I’ve decided to concentrate on structure and form.

It’s easy to get lost in the weeds when working through The Story Grid methodology. The related Story Grid podcast is a godsend in putting the rules of form and structure into perspective.

Restructuring From Chaos

In the last week, I’ve been trying to structure my Scrivener project to make it Story Grid compatible. Now, I can’t yet tell if this will help me achieve my goal of having a first draft that sort of works. But if it does work out, it’ll be a significant time-saver for the first editing phase.

Until recently, I’ve been chaotically writing prototype Scenes. Every week, I swapped and changed the order of the scenes to ‘work,’ then swapped them all back again later. Very frustrating.

I had several Scenes in progress for the first Act and one or two Scenes in progress for the other Acts, but none were at a stage that could be considered first-draft-ready.

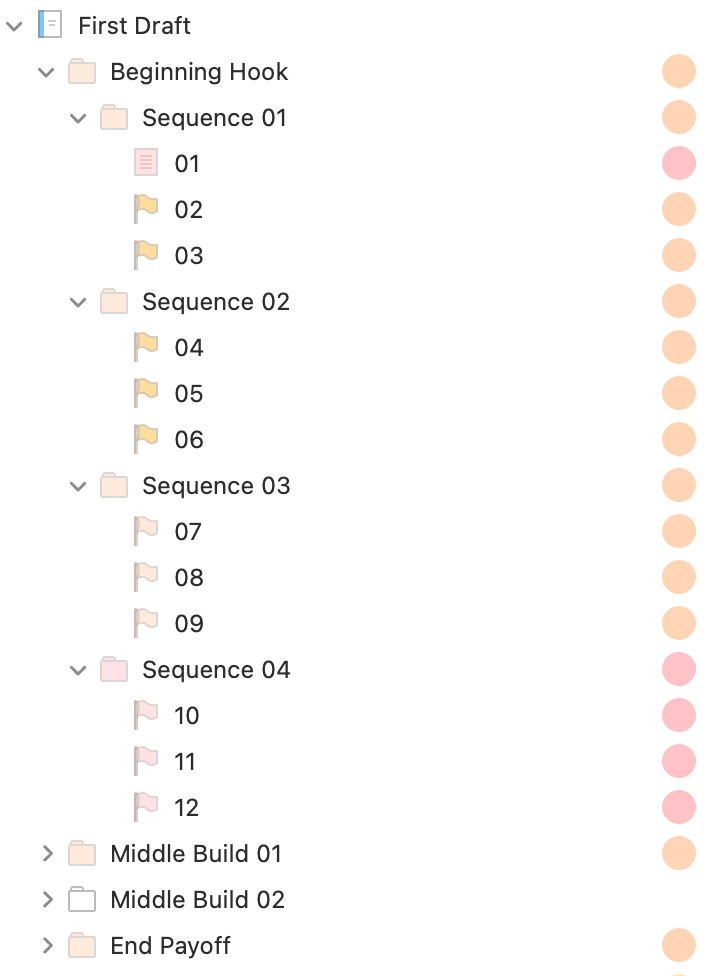

The game plan is to restructure the entire Scrivener project into three acts: the Beginning Hook, the Middle Build, and the Ending Payoff. It goes even further by dividing the Scenes into Sequences. For example:

From this screenshot, we can extrapolate that the Beginning Hook is planned to have twelve Scenes, representing twenty-five percent of the book. Remembering the rule of thumb of a 25-50-25 percent split for the three parts, we come to forty-eight scenes, each targeting fifteen hundred words. So, the project target will be seventy-two thousand words.

This is encouraging. If we write only two Scenes a week, the first draft will take around twenty-four weeks. Two Scenes every week seem more achievable than thinking about seventy-two thousand words.

Building Writing Momentum

As I’m writing every Scene, I should only have two things in my mind (apart from the story I’m telling):

Does it work?

Does it meet the five commandments of storytelling?

We want to build momentum and keep that momentum driving us forward. We must avoid stopping, rewinding, and fixing everything we may see as needing improvement. Make a note, then carry on.

In episode sixty-six of the Story Grid podcast, Tim Grahl says (edited):

“I stop and fix something when I'm breaking one of the five commandments of storytelling. Or when I'm obviously missing a major piece of the story. Churning on something until it meets the Story Grid conventions is worth it. And then once it's there and it works, it's time to move on.”

This brings me back to the five commandments of storytelling I mentioned in the last newsletter. In brief, every Scene must contain every one of these commandments:

An Inciting Incident.

A Progressive Complication.

A Crisis.

A Climax.

A Resolution.

It gets even more interesting when we realize that all five commandments must also be contained in every Sequence (of Scenes), each Act (Beginning, Middle, and End), and, of course, globally for the entire novel.

Starting From Scratch (Sort Of)

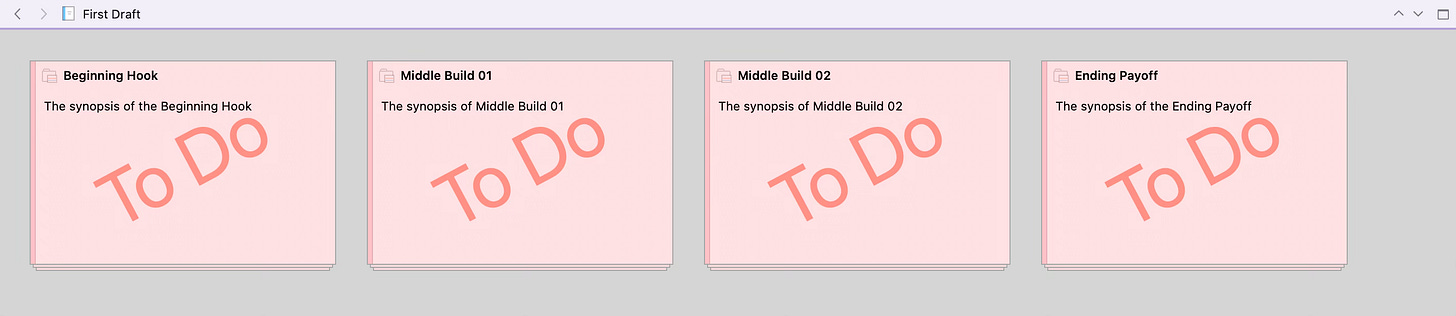

Now, while I’m not going to throw away the Scenes already in progress, at least not yet, it’s time to take a step back and work out a more detailed outline. Scrivener is the perfect tool for this; the corkboard or group mode allows me to visualize the entire structure together with the synopses of every part.

Here are three screenshots taken from the Scrivener project. First, the top level is where we can write the synopses for the main parts (Acts) of the novel:

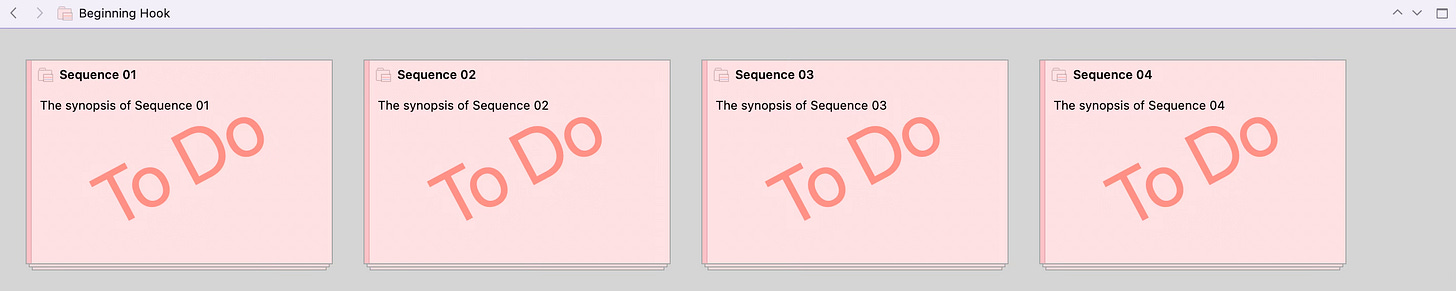

We can then drill down into each Act, for example, the Beginning Hook. Here, we can expand the synopsis of the Act to the level of the Sequences:

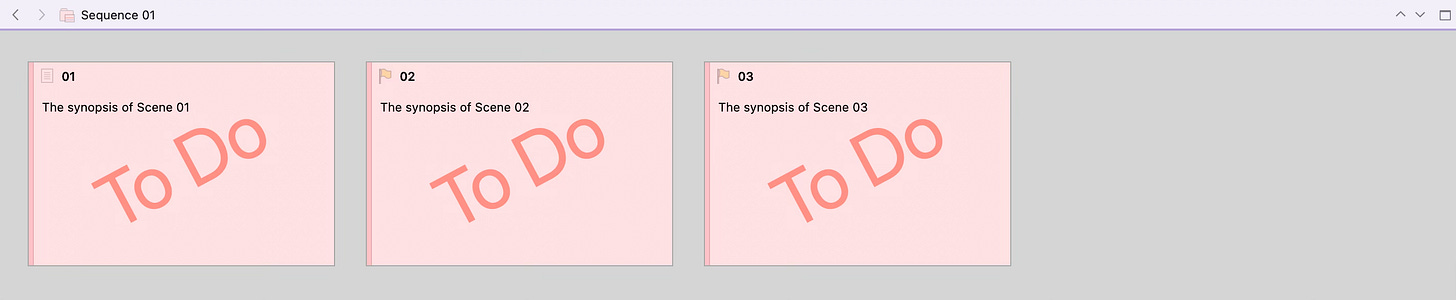

Finally, we have the deepest level of detailing the synopses of each Scene within the Sequence:

I’ve tried writing as a pantser or discovery writer, but it doesn’t work for me. Then, I tried a hybrid approach, where I roughly outlined a small part and wrote the appropriate Scenes. I kept jumping back and forth between the Scenes, even changing and rechanging their ordering.

Finally, I feel most comfortable with the plotter approach. I have to get on with it now.

Wish me luck.

Final Thoughts

I found the two Story Grid podcast episodes (episodes 35 and 36) with Steven Pressfield inspiring, but not for the obvious reasons that he is a successful author. He published his first book at fifty-five and, by eighty, had written or co-written twenty more—ten fiction and ten nonfiction.

I’ll be celebrating my sixty-fourth birthday in a few weeks, which gives me hope that my efforts will not be a complete waste of time. If Steven Pressfield can do it, I’ll do my damndest to emulate him.

Hopefully, you enjoyed this post. If you want to say ‘thank you, ‘ the best way is to get involved in the comments. And my promise to you…If you get in touch, I will answer! So comment away… (a subscription is also nice)